what wavelength is expected for light composed of photons produced by an n 3 to n 1

Atomic Construction

61 Atomic Spectra and X-rays

Learning Objectives

By the terminate of this section, yous will be able to:

- Depict the absorption and emission of radiation in terms of atomic energy levels and energy differences

- Use quantum numbers to gauge the energy, frequency, and wavelength of photons produced by atomic transitions in multi-electron atoms

- Explain radiation concepts in the context of atomic fluorescence and Ten-rays

The study of diminutive spectra provides almost of our cognition about atoms. In modernistic science, atomic spectra are used to place species of atoms in a range of objects, from distant galaxies to blood samples at a crime scene.

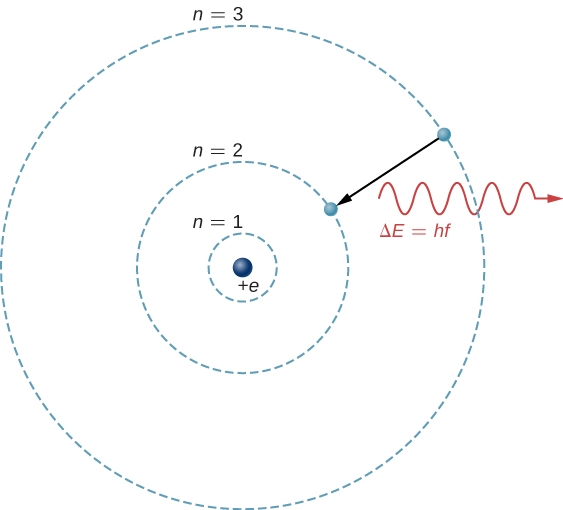

The theoretical basis of atomic spectroscopy is the transition of electrons between free energy levels in atoms. For example, if an electron in a hydrogen atom makes a transition from the ![]() to the

to the ![]() crush, the atom emits a photon with a wavelength

crush, the atom emits a photon with a wavelength

![]()

where ![]() is free energy carried away by the photon and

is free energy carried away by the photon and ![]() . After this radiation passes through a spectrometer, it appears every bit a sharp spectral line on a screen. The Bohr model of this procedure is shown in (Figure). If the electron afterwards absorbs a photon with energy

. After this radiation passes through a spectrometer, it appears every bit a sharp spectral line on a screen. The Bohr model of this procedure is shown in (Figure). If the electron afterwards absorbs a photon with energy ![]() , the electron returns to the

, the electron returns to the ![]() trounce. (We examined the Bohr model earlier, in Photons and Affair Waves.)

trounce. (We examined the Bohr model earlier, in Photons and Affair Waves.)

An electron transition from the ![]() to the

to the ![]() shell of a hydrogen atom.

shell of a hydrogen atom.

To understand diminutive transitions in multi-electron atoms, information technology is necessary to consider many effects, including the Coulomb repulsion between electrons and internal magnetic interactions (spin-orbit and spin-spin couplings). Fortunately, many properties of these systems can exist understood by neglecting interactions between electrons and representing each electron by its own single-particle moving ridge function ![]() .

.

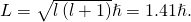

Atomic transitions must obey option rules. These rules follow from principles of quantum mechanics and symmetry. Selection rules allocate transitions as either allowed or forbidden. (Forbidden transitions do occur, simply the probability of the typical forbidden transition is very modest.) For a hydrogen-like cantlet, diminutive transitions that involve electromagnetic interactions (the emission and absorption of photons) obey the following pick rule:

![]()

where fifty is associated with the magnitude of orbital athwart momentum,

![]()

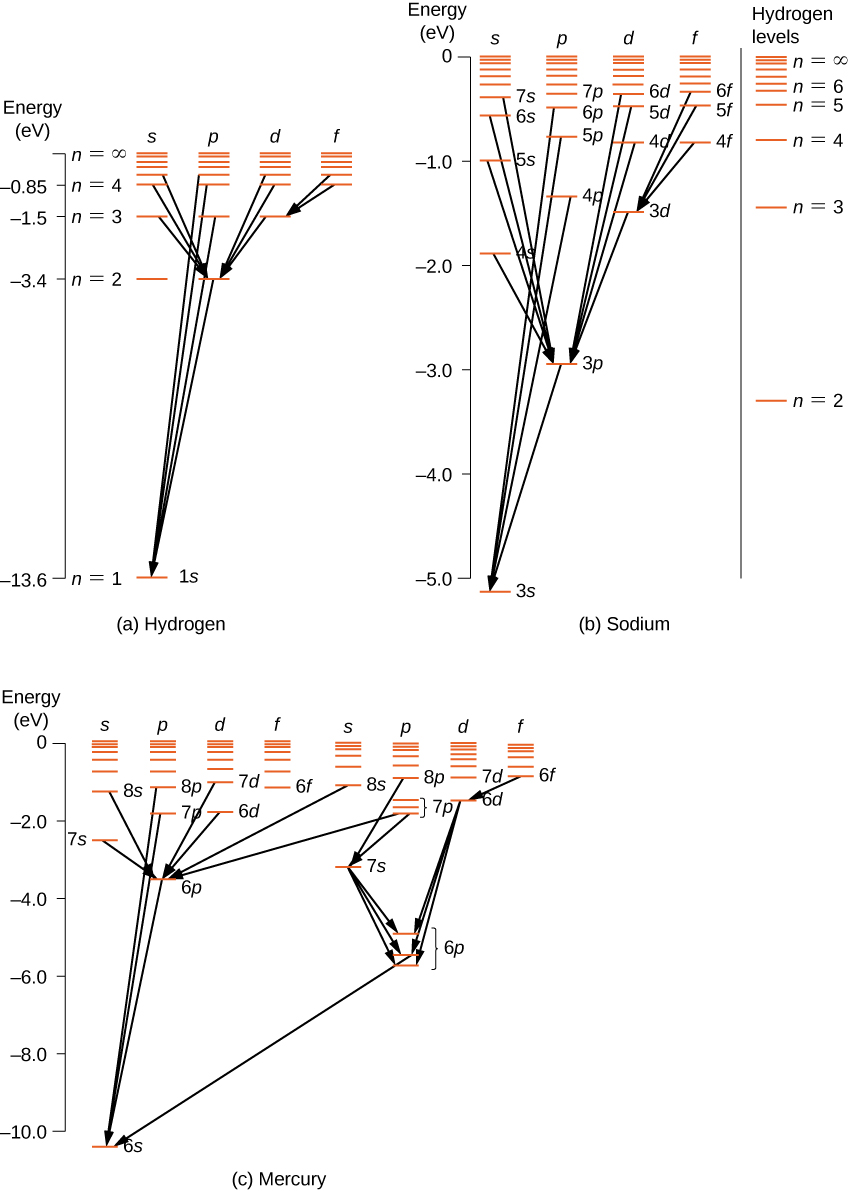

For multi-electron atoms, like rules utilize. To illustrate this rule, consider the observed atomic transitions in hydrogen (H), sodium (Na), and mercury (Hg) ((Figure)). The horizontal lines in this diagram correspond to atomic energy levels, and the transitions immune by this option dominion are shown by lines fatigued betwixt these levels. The energies of these states are on the society of a few electron volts, and photons emitted in transitions are in the visible range. Technically, atomic transitions can violate the choice rule, simply such transitions are uncommon.

Energy-level diagrams for (a) hydrogen, (b) sodium, and (c) mercury. For comparison, hydrogen energy levels are shown in the sodium diagram.

The hydrogen atom has the simplest energy-level diagram. If nosotros neglect electron spin, all states with the same value of n take the same full energy. However, spin-orbit coupling splits the ![]() states into two angular momentum states (due south and p) of slightly different energies. (These levels are not vertically displaced, because the free energy splitting is too modest to testify up in this diagram.) As well, spin-orbit coupling splits the

states into two angular momentum states (due south and p) of slightly different energies. (These levels are not vertically displaced, because the free energy splitting is too modest to testify up in this diagram.) As well, spin-orbit coupling splits the ![]() states into three athwart momentum states (s, p, and d).

states into three athwart momentum states (s, p, and d).

The energy-level diagram for hydrogen is similar to sodium, because both atoms have 1 electron in the outer shell. The valence electron of sodium moves in the electrical field of a nucleus shielded past electrons in the inner shells, so it does not experience a simple one/r Coulomb potential and its total energy depends on both due north and l. Interestingly, mercury has two carve up energy-level diagrams; these diagrams correspond to two net spin states of its 6southward (valence) electrons.

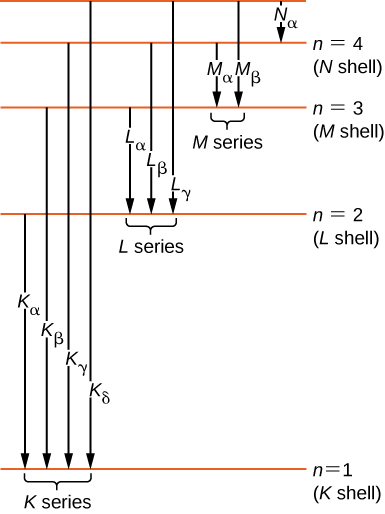

The Sodium Doublet The spectrum of sodium is analyzed with a spectrometer. Two closely spaced lines with wavelengths 589.00 nm and 589.59 nm are observed. (a) If the doublet corresponds to the excited (valence) electron that transitions from some excited country down to the 3s state, what was the original electron angular momentum? (b) What is the energy difference betwixt these two excited states?

Strategy Sodium and hydrogen belong to the aforementioned cavalcade or chemical group of the periodic table, so sodium is "hydrogen-like." The outermost electron in sodium is in the threes (![]() ) subshell and can be excited to higher energy levels. As for hydrogen, subsequent transitions to lower energy levels must obey the choice rule:

) subshell and can be excited to higher energy levels. As for hydrogen, subsequent transitions to lower energy levels must obey the choice rule:

![]()

We must first make up one's mind the breakthrough number of the initial state that satisfies the option rule. Then, nosotros tin use this number to determine the magnitude of orbital angular momentum of the initial state.

Solution

- Allowed transitions must obey the selection rule. If the quantum number of the initial state is

, the transition is forbidden because

, the transition is forbidden because  . If the quantum number of the initial land is

. If the quantum number of the initial land is  ,…the transition is forbidden because

,…the transition is forbidden because  Therefore, the quantum of the initial state must be

Therefore, the quantum of the initial state must be  . The orbital athwart momentum of the initial country is

. The orbital athwart momentum of the initial country is

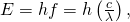

- Because the final state for both transitions is the same (3s), the departure in energies of the photons is equal to the difference in energies of the two excited states. Using the equation

we have

Significance To empathise the difficulty of measuring this energy difference, nosotros compare this departure with the average energy of the two photons emitted in the transition. Given an boilerplate wavelength of 589.xxx nm, the average energy of the photons is

![]()

The free energy difference ![]() is about 0.1% (1 part in thou) of this average free energy. However, a sensitive spectrometer can measure the difference.

is about 0.1% (1 part in thou) of this average free energy. However, a sensitive spectrometer can measure the difference.

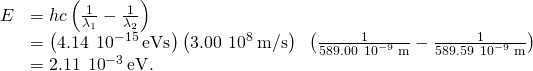

Diminutive Fluorescence

Fluorescence occurs when an electron in an atom is excited several steps higher up the ground state by the absorption of a loftier-free energy ultraviolet (UV) photon. One time excited, the electron "de-excites" in two ways. The electron tin can drop dorsum to the basis state, emitting a photon of the same energy that excited information technology, or it can drop in a series of smaller steps, emitting several low-energy photons. Some of these photons may be in the visible range. Fluorescent dye in clothes can make colors seem brighter in sunlight by converting UV radiation into visible light. Fluorescent lights are more efficient in converting electrical energy into visible lite than incandescent filaments (nigh four times every bit efficient). (Figure) shows a scorpion illuminated by a UV lamp. Proteins near the surface of the skin emit a characteristic blue light.

A scorpion glows blueish under a UV lamp. (credit: Ken Bosma)

X-rays

The study of atomic energy transitions enables us to understand X-rays and 10-ray engineering science. Similar all electromagnetic radiation, X-rays are made of photons. X-ray photons are produced when electrons in the outermost shells of an cantlet drop to the inner shells. (Hydrogen atoms do non emit X-rays, considering the electron energy levels are too closely spaced together to allow the emission of high-frequency radiation.) Transitions of this kind are ordinarily forbidden because the lower states are already filled. Still, if an inner shell has a vacancy (an inner electron is missing, perchance from being knocked away past a loftier-speed electron), an electron from one of the outer shells can driblet in energy to fill the vacancy. The energy gap for such a transition is relatively large, so wavelength of the radiated X-ray photon is relatively brusk.

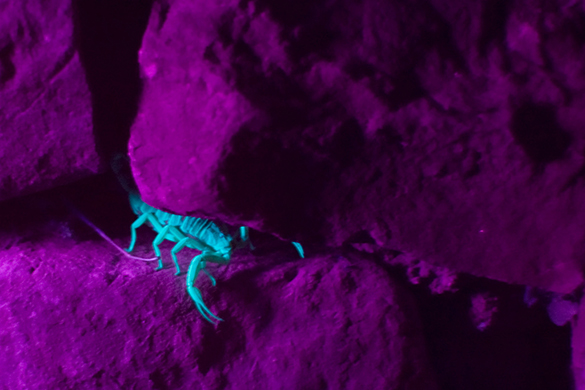

X-rays can also exist produced by bombarding a metal target with high-energy electrons, equally shown in (Figure). In the figure, electrons are boiled off a filament and accelerated by an electrical field into a tungsten target. Co-ordinate to the classical theory of electromagnetism, any charged particle that accelerates emits radiation. Thus, when the electron strikes the tungsten target, and all of a sudden slows down, the electron emits braking radiation. (Braking radiation refers to radiations produced by any charged particle that is slowed by a medium.) In this example, braking radiation contains a continuous range of frequencies, because the electrons will collide with the target atoms in slightly dissimilar ways.

Braking radiation is not the only type of radiation produced in this interaction. In some cases, an electron collides with some other inner-crush electron of a target cantlet, and knocks the electron out of the atom—billiard brawl way. The empty land is filled when an electron in a college beat drops into the land (drop in free energy level) and emits an X-ray photon.

A sketch of an X-ray tube. X-rays are emitted from the tungsten target.

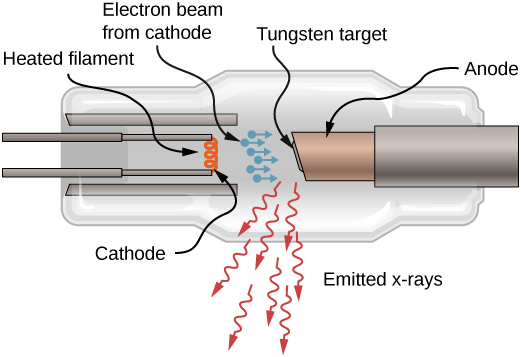

Historically, X-ray spectral lines were labeled with messages (Thousand, L, Chiliad, N, …). These letters correspond to the diminutive shells (![]() ). X-rays produced by a transition from any higher shell to the K (

). X-rays produced by a transition from any higher shell to the K (![]() ) beat out are labeled every bit 1000 X-rays. X-rays produced in a transition from the Fifty (

) beat out are labeled every bit 1000 X-rays. X-rays produced in a transition from the Fifty (![]() ) beat out are called

) beat out are called ![]() 10-rays; Ten-rays produced in a transition from the M (

10-rays; Ten-rays produced in a transition from the M (![]() ) beat out are called

) beat out are called ![]() X-rays; X-rays produced in a transition from the N (

X-rays; X-rays produced in a transition from the N (![]() ) crush are chosen

) crush are chosen ![]() Ten-rays; and then forth. Transitions from college shells to Fifty and Grand shells are labeled similarly. These transitions are represented by an energy-level diagram in (Effigy).

Ten-rays; and then forth. Transitions from college shells to Fifty and Grand shells are labeled similarly. These transitions are represented by an energy-level diagram in (Effigy).

Ten-ray transitions in an cantlet.

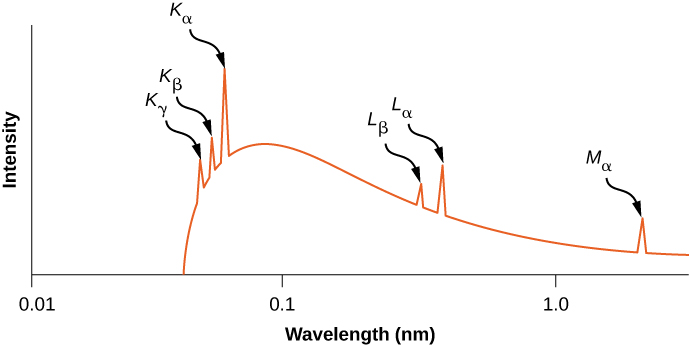

The distribution of X-ray wavelengths produced by striking metallic with a beam of electrons is given in (Effigy). X-ray transitions in the target metallic appear every bit peaks on pinnacle of the braking radiation bend. Photon frequencies corresponding to the spikes in the X-ray distribution are called characteristic frequencies, considering they tin exist used to identify the target metallic. The abrupt cutoff wavelength (only beneath the ![]() acme) corresponds to an electron that loses all of its free energy to a single photon. Radiations of shorter wavelengths is forbidden by the conservation of free energy.

acme) corresponds to an electron that loses all of its free energy to a single photon. Radiations of shorter wavelengths is forbidden by the conservation of free energy.

X-ray spectrum from a silvery target. The peaks represent to feature frequencies of X-rays emitted by silver when struck past an electron beam.

10-Rays from Aluminum Estimate the characteristic energy and frequency of the ![]() X-ray for aluminum (

X-ray for aluminum (![]() ).

).

Strategy A ![]() 10-ray is produced by the transition of an electron in the L (

10-ray is produced by the transition of an electron in the L (![]() ) vanquish to the Thou (

) vanquish to the Thou (![]() ) shell. An electron in the Fifty shell "sees" a charge

) shell. An electron in the Fifty shell "sees" a charge ![]() because one electron in the K crush shields the nuclear charge. (Retrieve, two electrons are not in the K shell because the other electron state is vacant.) The frequency of the emitted photon can be estimated from the energy difference between the 50 and Thou shells.

because one electron in the K crush shields the nuclear charge. (Retrieve, two electrons are not in the K shell because the other electron state is vacant.) The frequency of the emitted photon can be estimated from the energy difference between the 50 and Thou shells.

Solution The free energy difference between the L and One thousand shells in a hydrogen atom is 10.2 eV. Assuming that other electrons in the L shell or in higher-free energy shells do non shield the nuclear charge, the free energy departure between the Fifty and K shells in an atom with ![]() is approximately

is approximately

![]()

Based on the human relationship ![]() , the frequency of the Ten-ray is

, the frequency of the Ten-ray is

![]()

Significance The wavelength of the typical X-ray is 0.ane–ten nm. In this case, the wavelength is:

![]()

Hence, the transition L ![]() Thousand in aluminum produces X-ray radiation.

Thousand in aluminum produces X-ray radiation.

X-ray production provides an of import test of quantum mechanics. According to the Bohr model, the free energy of a ![]() 10-ray depends on the nuclear accuse or atomic number, Z. If Z is big, Coulomb forces in the atom are large, free energy differences (

10-ray depends on the nuclear accuse or atomic number, Z. If Z is big, Coulomb forces in the atom are large, free energy differences (![]() ) are large, and, therefore, the energy of radiated photons is large. To illustrate, consider a single electron in a multi-electron cantlet. Neglecting interactions betwixt the electrons, the allowed energy levels are

) are large, and, therefore, the energy of radiated photons is large. To illustrate, consider a single electron in a multi-electron cantlet. Neglecting interactions betwixt the electrons, the allowed energy levels are

![]()

where n = ane, ii, …and Z is the diminutive number of the nucleus. Notwithstanding, an electron in the Fifty (![]() ) shell "sees" a accuse

) shell "sees" a accuse ![]() , considering one electron in the K shell shields the nuclear charge. (Remember that in that location is but one electron in the Grand shell because the other electron was "knocked out.") Therefore, the guess energies of the electron in the L and Chiliad shells are

, considering one electron in the K shell shields the nuclear charge. (Remember that in that location is but one electron in the Grand shell because the other electron was "knocked out.") Therefore, the guess energies of the electron in the L and Chiliad shells are

The free energy carried abroad past a photon in a transition from the L beat out to the Grand trounce is therefore

![]()

where Z is the atomic number. In general, the 10-ray photon free energy for a transition from an outer shell to the Chiliad trounce is

![]()

or

![]()

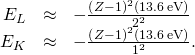

where f is the frequency of a ![]() X-ray. This equation is Moseley'southward law. For large values of Z, we have approximately

X-ray. This equation is Moseley'southward law. For large values of Z, we have approximately

![]()

This prediction can be checked past measuring f for a variety of metal targets. This model is supported if a plot of Z versus ![]() data (called a Moseley plot) is linear. Comparison of model predictions and experimental results, for both the K and L series, is shown in (Figure). The data support the model that X-rays are produced when an outer beat electron drops in energy to fill up a vacancy in an inner beat out.

data (called a Moseley plot) is linear. Comparison of model predictions and experimental results, for both the K and L series, is shown in (Figure). The data support the model that X-rays are produced when an outer beat electron drops in energy to fill up a vacancy in an inner beat out.

Check Your Understanding X-rays are produced by bombarding a metal target with high-energy electrons. If the target is replaced by another with two times the diminutive number, what happens to the frequency of Ten-rays?

frequency quadruples

A Moseley plot. These data were adapted from Moseley'south original information (H. G. J. Moseley, Philos. Mag. (6) 77:703, 1914).

Characteristic 10-Ray Energy Calculate the approximate energy of a ![]() Ten-ray from a tungsten anode in an 10-ray tube.

Ten-ray from a tungsten anode in an 10-ray tube.

Strategy Two electrons occupy a filled K shell. A vacancy in this shell would leave one electron, so the constructive charge for an electron in the L trounce would exist Z − 1 rather than Z. For tungsten, ![]() then the effective charge is 73. This number can exist used to calculate the free energy-level difference between the 50 and K shells, and, therefore, the energy carried away past a photon in the transition

then the effective charge is 73. This number can exist used to calculate the free energy-level difference between the 50 and K shells, and, therefore, the energy carried away past a photon in the transition ![]()

Solution The effective Z is 73, so the ![]() X-ray energy is given by

X-ray energy is given by

![]()

where

![]()

and

![]()

Thus,

![]()

Significance This large photon energy is typical of Ten-rays. X-ray energies become progressively larger for heavier elements considering their energy increases approximately equally ![]() . An acceleration voltage of more than l,000 volts is needed to "knock out" an inner electron from a tungsten atom.

. An acceleration voltage of more than l,000 volts is needed to "knock out" an inner electron from a tungsten atom.

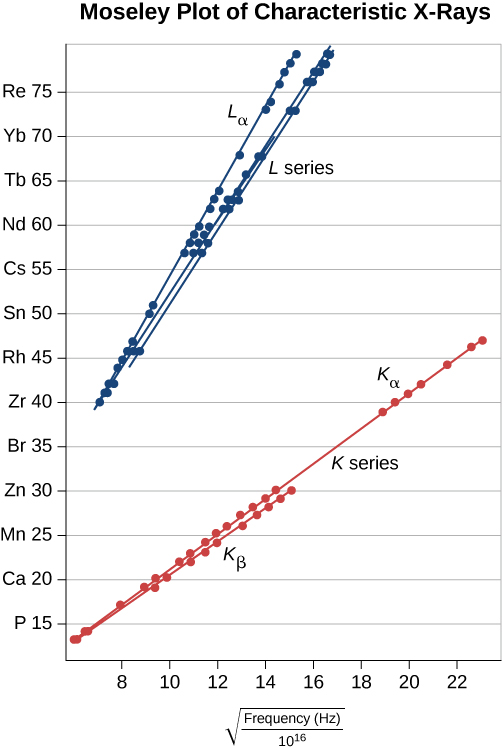

X-ray Technology

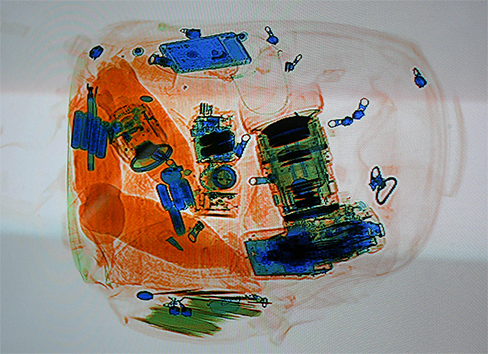

X-rays have many applications, such as in medical diagnostics ((Effigy)), inspection of luggage at airports ((Figure)), and even detection of cracks in crucial shipping components. The most mutual X-ray images are due to shadows. Because X-ray photons have high energy, they penetrate materials that are opaque to visible light. The more energy an X-ray photon has, the more than textile it penetrates. The depth of penetration is related to the density of the material, too as to the energy of the photon. The denser the textile, the fewer X-ray photons get through and the darker the shadow. X-rays are effective at identifying bone breaks and tumors; however, overexposure to X-rays can impairment cells in biological organisms.

(a) An X-ray image of a person's teeth. (b) A typical X-ray machine in a dentist's role produces relatively low-energy radiation to minimize patient exposure. (credit a: modification of work by "Dmitry G"/Wikimedia Commons)

An X-ray image of a piece of baggage. The denser the material, the darker the shadow. Object colors relate to textile composition—metal objects show up every bit blue in this prototype. (credit: "IDuke"/Wikimedia Eatables)

A standard X-ray image provides a ii-dimensional view of the object. All the same, in medical applications, this view does not ofttimes provide enough data to draw firm conclusions. For instance, in a two-dimensional X-ray image of the body, bones can easily hide soft tissues or organs. The CAT (computed axial tomography) scanner addresses this problem past collecting numerous Ten-ray images in "slices" throughout the trunk. Complex computer-image processing of the relative absorption of the Ten-rays, in different directions, tin can produce a highly detailed three-dimensional X-ray paradigm of the trunk.

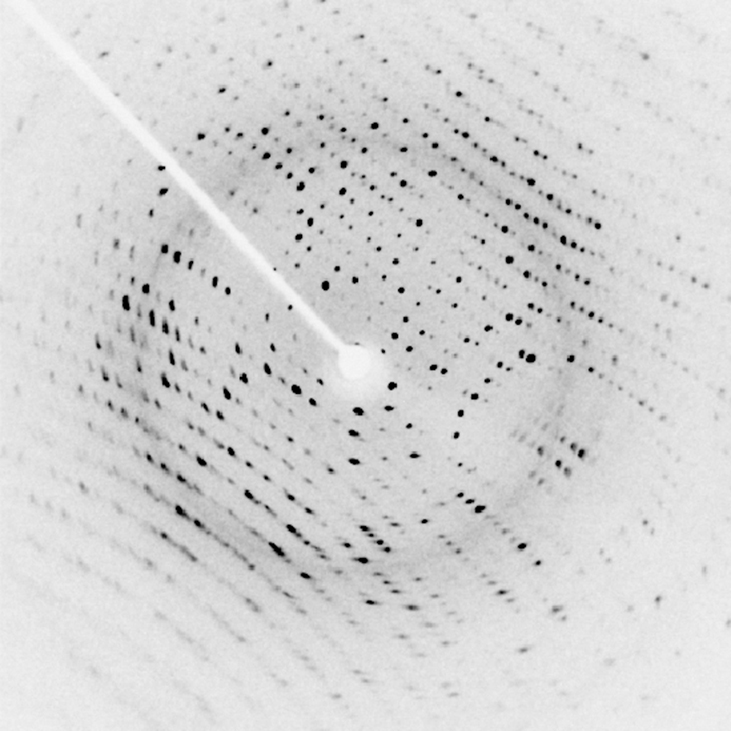

X-rays tin also exist used to probe the structures of atoms and molecules. Consider X-rays incident on the surface of a crystalline solid. Some X-ray photons reflect at the surface, and others reflect off the "aeroplane" of atoms just beneath the surface. Interference between these photons, for different angles of incidence, produces a beautiful image on a screen ((Effigy)). The interaction of 10-rays with a solid is called 10-ray diffraction. The most famous example using Ten-ray diffraction is the discovery of the double-helix structure of DNA.

X-ray diffraction from the crystal of a protein (hen egg lysozyme) produced this interference pattern. Assay of the pattern yields information about the structure of the protein. (credit: "Del45"/Wikimedia Commons)

Summary

- Radiation is absorbed and emitted by atomic energy-level transitions.

- Quantum numbers can be used to estimate the free energy, frequency, and wavelength of photons produced by diminutive transitions.

- Atomic fluorescence occurs when an electron in an atom is excited several steps above the ground land past the absorption of a high-energy ultraviolet (UV) photon.

- X-ray photons are produced when a vacancy in an inner shell of an atom is filled by an electron from the outer shell of the atom.

- The frequency of 10-ray radiation is related to the atomic number Z of an atom.

Conceptual Questions

Diminutive and molecular spectra are discrete. What does discrete mean, and how are discrete spectra related to the quantization of energy and electron orbits in atoms and molecules?

Atomic and molecular spectra are said to exist "discrete," because only certain spectral lines are observed. In dissimilarity, spectra from a white light source (consisting of many photon frequencies) are continuous considering a continuous "rainbow" of colors is observed.

Hash out the procedure of the absorption of calorie-free by matter in terms of the atomic structure of the absorbing medium.

NGC1763 is an emission nebula in the Big Magellanic Cloud simply outside our Milky Mode Galaxy. Ultraviolet light from hot stars ionize the hydrogen atoms in the nebula. As protons and electrons recombine, light in the visible range is emitted. Compare the energies of the photons involved in these two transitions.

UV light consists of relatively high frequency (brusque wavelength) photons. So the energy of the absorbed photon and the free energy transition (![]() ) in the atom is relatively large. In comparison, visible calorie-free consists of relatively lower-frequency photons. Therefore, the free energy transition in the atom and the energy of the emitted photon is relatively pocket-sized.

) in the atom is relatively large. In comparison, visible calorie-free consists of relatively lower-frequency photons. Therefore, the free energy transition in the atom and the energy of the emitted photon is relatively pocket-sized.

Why are X-rays emitted but for electron transitions to inner shells? What blazon of photon is emitted for transitions between outer shells?

How do the allowed orbits for electrons in atoms differ from the allowed orbits for planets around the sun?

For macroscopic systems, the quantum numbers are very big, then the energy difference (![]() ) between adjacent energy levels (orbits) is very small. The energy released in transitions between these closely space energy levels is much too small to be detected.

) between adjacent energy levels (orbits) is very small. The energy released in transitions between these closely space energy levels is much too small to be detected.

Bug

The cherry light emitted past a ruby laser has a wavelength of 694.3 nm. What is the difference in free energy between the initial state and last state corresponding to the emission of the light?

The wavelength of the laser is given by:

![]()

where ![]() is the free energy of the photon and

is the free energy of the photon and ![]() is the magnitude of the energy difference. Solving for the latter, nosotros get:

is the magnitude of the energy difference. Solving for the latter, nosotros get:

![]()

The negative sign indicates that the electron lost free energy in the transition.

The xanthous lite from a sodium-vapor street lamp is produced by a transition of sodium atoms from a threep land to a 3s state. If the difference in energies of those ii states is 2.10 eV, what is the wavelength of the yellow light?

Approximate the wavelength of the ![]() X-ray from calcium.

X-ray from calcium.

![]()

Estimate the frequency of the ![]() X-ray from cesium.

X-ray from cesium.

X-rays are produced past striking a target with a beam of electrons. Prior to striking the target, the electrons are accelerated by an electric field through a potential energy difference:

![]()

where e is the charge of an electron and ![]() is the voltage deviation. If

is the voltage deviation. If ![]() volts, what is the minimum wavelength of the emitted radiation?

volts, what is the minimum wavelength of the emitted radiation?

Co-ordinate to the conservation of the free energy, the potential free energy of the electron is converted completely into kinetic free energy. The initial kinetic energy of the electron is zippo (the electron begins at remainder). And then, the kinetic energy of the electron merely before it strikes the target is:

![]()

If all of this free energy is converted into braking radiation, the frequency of the emitted radiation is a maximum, therefore:

![]()

When the emitted frequency is a maximum, so the emitted wavelength is a minimum, so:

![]()

For the preceding trouble, what happens to the minimum wavelength if the voltage across the Ten-ray tube is doubled?

Suppose the experiment in the preceding trouble is conducted with muons. What happens to the minimum wavelength?

A muon is 200 times heavier than an electron, just the minimum wavelength does not depend on mass, so the result is unchanged.

An Ten-ray tube accelerates an electron with an practical voltage of 50 kV toward a metallic target. (a) What is the shortest-wavelength 10-ray radiation generated at the target? (b) Calculate the photon free energy in eV. (c) Explicate the relationship of the photon energy to the practical voltage.

A color television tube generates some X-rays when its electron beam strikes the screen. What is the shortest wavelength of these X-rays, if a xxx.0-kV potential is used to accelerate the electrons? (Note that TVs take shielding to prevent these X-rays from exposing viewers.)

![]()

An 10-ray tube has an applied voltage of 100 kV. (a) What is the most energetic X-ray photon it tin produce? Express your answer in electron volts and joules. (b) Notice the wavelength of such an X-ray.

The maximum characteristic 10-ray photon energy comes from the capture of a free electron into a K shell vacancy. What is this photon energy in keV for tungsten, assuming that the gratis electron has no initial kinetic energy?

72.5 keV

What are the approximate energies of the ![]() and

and ![]() X-rays for copper?

X-rays for copper?

Compare the X-ray photon wavelengths for copper and gold.

The diminutive numbers for Cu and Au are ![]() and 79, respectively. The 10-ray photon frequency for golden is greater than copper by a factor:

and 79, respectively. The 10-ray photon frequency for golden is greater than copper by a factor:

![]()

Therefore, the X-ray wavelength of Au is about viii times shorter than for copper.

Glossary

- braking radiation

- radiations produced by targeting metallic with a high-energy electron axle (or radiation produced by the acceleration of any charged particle in a textile)

- fluorescence

- radiation produced by the excitation and subsequent, gradual de-excitation of an electron in an atom

- Moseley's law

- relationship between the atomic number and X-ray photon frequency for Ten-ray product

- Moseley plot

- plot of the diminutive number versus the square root of X-ray frequency

- selection rules

- rules that decide whether atomic transitions are allowed or forbidden (rare)

huxhamfriontromes.blogspot.com

Source: https://opentextbc.ca/universityphysicsv3openstax/chapter/atomic-spectra-and-x-rays/

0 Response to "what wavelength is expected for light composed of photons produced by an n 3 to n 1"

Post a Comment